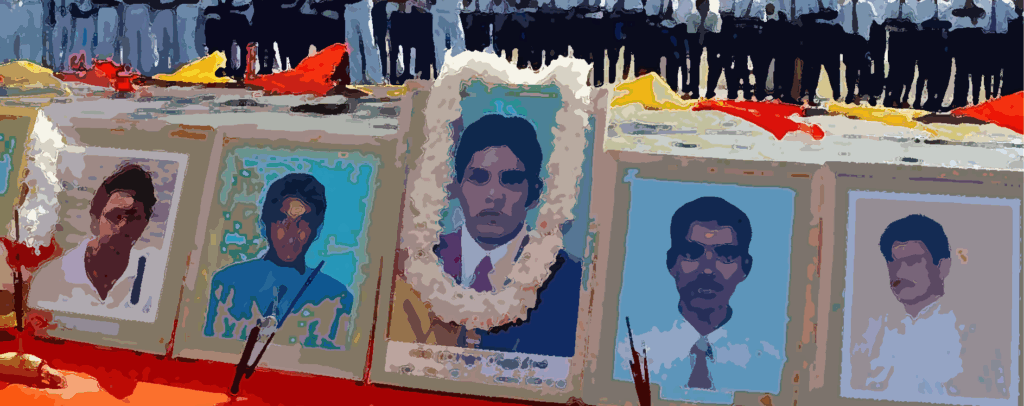

Trinco Five: The Murder of Five Tamil Students

On 2nd January 2006, seven young men sat near the Gandhi statue in Trincomalee, celebrating the New Year. Some had just received university admission letters. By nightfall, five were dead, shot execution-style while under the watch of Sri Lankan security forces.

This case is critical not only because of its brutality but also because of its systematic cover-up, orchestrated from the top, that ultimately resulted in complete impunity for those responsible.

Almost 20 years later, no one has been held accountable.

The Night in Question: A 20-Minute Window

7:35 PM: A green auto-rickshaw throws a grenade at the students and drives straight into Fort Frederick—the Army headquarters. The Navy immediately seals both exits from the beach area.

7:35-7:55 PM: Security forces control the scene. For twenty minutes, no medical assistance arrives. Parents trying to reach their sons are turned back.

7:55 PM: A vehicle approaches with only parking lights on. Armed men emerge. Survivor Yoganathan Poongulalon testified that after beating the injured students, someone in the vehicle barked an order: Kill them. The gunfire lasted over a minute. When the headlights switched on, two more students, who’d been desperately seeking help, were spotted and shot.

The Cover-up

Dr Manoharan, father of one of the students, heard the blast from his home that evening, just 300 meters from the beach. He rushed to the scene, but navy guards blocked his way. Hours later, he went to the mortuary.

When he opened the door, the first body he saw was his son Ragihar’s, with five gunshot wounds visible. A police officer immediately demanded that he sign a statement claiming Ragihar belonged to the LTTE. In exchange, they’d release the body.

He refused. “My son is not a Tamil Tiger. He is a sports person, a table tennis player and coach—he coaches police officers and children. He is a chess player, a student, a good boy.”

The government’s narrative suggested that the deceased were members of the LTTE who had accidentally triggered the grenades they were carrying. However, this explanation quickly began to fall apart. Three of the young men had been shot through the back of the head at close range. Dr Manoharan’s photographs and the doctor’s report confirmed it: small entry wounds, large exit wounds, the unmistakable signature of execution-style killings.

But what Dr Manoharan faced in the mortuary wasn’t isolated pressure; it was systematic:

- All police phone lines went unanswered during the attack, despite multiple citizens attempting to call for help.

- Bullet casings mysteriously appeared two days later, only after international media reported the truth about gunshot wounds.

- The official narrative persisted even after forensic evidence proved otherwise, with some officials continuing to claim grenade blast injuries.

- Senior officials were never held responsible. SP Kapila Jayasekere’s presence at the scene was confirmed by multiple witnesses. His unmarked vehicle was photographed near the scene before the shooting. Rather than face prosecution, he was promoted to SSP and later entrusted with investigating another massacre, the killing of 17 ACF aid workers in Mutur in August 2006.

- Witnesses were systematically silenced. The green auto-rickshaw from which the grenade was thrown was traced to someone connected to home guards and the criminal underworld, regularly parked near police headquarters. Balachandran, an auto-rickshaw driver who helped families identify the vehicle and its connections to security forces, was killed in August 2006.

Significant dates from the case (Illustrated)

- 31st March 2003 – Report by High Court Judge T. Sunderalingam (appointed by the Sri Lanka Human Rights Commission) stated that “It is highly unlikely that anyone other than the Special Task Force (STF) could have shot those who were at the Gandhi statue.”

- August 2007 – The Udalgama commission collected evidence from witnesses, including those residing abroad. They reported that 13 personnel from the STF, along with IP VAS/Vas Perera and two naval officers in camouflage uniforms, were present at the crime scene. Based on this evidence, the report concluded that “there are strong grounds to surmise the involvement of uniformed personnel in the commission of the crime.” However, the commission didn’t accuse any individual.

- March – October 2013 – Dr. Kasipillai Manoharan, the father of Ragihar, and Aiyamuttu Shanmugarajah, the father of Gajendra, participated in several meetings and conferences during the UN Human Rights Council Sessions in Geneva. Their demands for justice had a significant impact, prompting Mahinda Samarasinghe, the then Plantation Industries Minister and head of the Sri Lankan delegation in Geneva, to advocate for an investigation. As a result, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) resumed its inquiry.

- July 4th, 2013 – 12 STF personnel and a police officer were arrested and produced in court. However, on the 14th of October 2013, they were all released on bail.

- 16th September 2015 – The OHCHR investigation on Sri Lanka determined that there were “reasonable grounds to believe that security personnel, including STF personnel, carried out the murder of the five students.”

- July 2019 – 8 of the 36 witnesses cited were not heard by the court, though they had made themselves available to testify. Among them were crucial witnesses, including two surviving eyewitnesses. Trincomalee Chief Magistrate M.M. Mohommed Hamza dismissed all charges against the 13 defendants, stating that there was insufficient evidence to satisfactorily proceed with the case. This conclusion brought an end to the Trinco 5 case.

- On 21st September 2025, Dr Kasipillai Manoharan passed away, leaving a profound impact on those who knew him and the cause he championed.

The Trinco Five case reveals the depth of the obstacles to accountability in Sri Lanka. Despite multiple investigations and survivor testimony, systemic challenges (witness intimidation, assassinations, and political obstruction) have prevented prosecution. The lasting impact on victims’ families and the broader community underscores an urgent need for transparency, genuine reform, and a legal system capable of prosecuting state crimes.