Sri Lanka’s Office for Reparations: Progress and Ongoing Challenges

Since its establishment in 2018, Sri Lanka’s Office for Reparations has distributed over Rs 9 billion to victims of conflict and violence. However, the institution continues to face the same structural issues that have hindered it since its predecessor agency was founded in 1987.

The Office for Reparations was created under Act No. 34 of 2018 as part of Sri Lanka’s transitional justice framework. Its mandate covers victims of the North East Conflict, political violence between 1994 and 2014, the Easter Sunday attacks in 2019, and various instances of civil unrest. Between 2018 and 2025, the office allocated Rs 1.5 billion for deaths and injuries, Rs 7.1 billion for property damage, and Rs 310 million in compensation payments up to June 2025.

In addition to providing financial relief, the office has endeavoured to rebuild livelihoods. It operates loan schemes in partnership with the Bank of Ceylon, granting 9,654 loans valued at Rs 1.6 billion between 2010 and August 2021. Training programs have been implemented to teach skills such as solar panel installation in Mannar and Vavuniya, palmyra handicraft in Jaffna, and handloom weaving in Batticaloa and Ampara. An Easter Attack Victim Fund was established following a Supreme Court order requiring six respondents to pay Rs 311 million in fines.

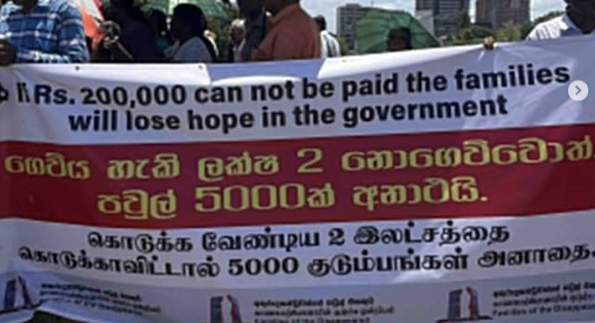

As of August 2025, the office has processed 4,572 of the 4,703 recommendations received from the Office on Missing Persons. Families of missing persons receive Rs 200,000 per individual, the same amount awarded for confirmed deaths.

Despite these efforts, the organisation faces constraints that limit its effectiveness. Its staff is drawn from a pool established for the Rehabilitation of Persons, Properties, and Industries Authority, created in 1983. The outdated recruitment structure and salary grades make it challenging to hire professionals with expertise in transitional justice or victim-centred policy design. Although the office’s mandate includes psychological support and community-based reparations, it lacks the human resources necessary to deliver these services at the required scale.

Centralisation exacerbates the issue. With services concentrated in Colombo, victims in remote and conflict-affected areas encounter barriers to access. Coordination with Divisional Secretariats, which identify eligible beneficiaries, has proven inefficient. The office has not updated beneficiary lists annually, resulting in continued payments to individuals who no longer qualify while excluding newly eligible recipients.

Reports indicate that politicisation and favouritism have impacted the beneficiary selection process, leading to an uneven distribution of reparations. The office now faces the challenge of managing competing community demands while upholding the transparency and fairness essential to transitional justice.

The Office for Reparations illustrates both the ambitions and limitations of institutional reform in post-conflict settings. It has provided substantial financial assistance and created livelihood opportunities for thousands. Whether it can overcome its structural weaknesses to fulfil its broader mandate remains to be seen.